A progressive bid to limit a less-useful initiative process

Plus dealing with that tort liability bomb and the latest on the Airbnb tax fight

There was a time when the biggest progressive players in Washington politics needed the ballot initiative because their ambitious and expensive ideas frequently fell flat in a closely divided Legislature.

Way back in 2000, the Washington Education Association persuaded voters to mandate annual cost-of-living increases for its member teachers. As recently as 2018, environmental groups went to the ballot with a carbon-pricing scheme. (Big Oil spent $30 million snuffing it out; a few years later the two sides kinda-sorta hugged it out over the Climate Commitment Act.) And perhaps the biggest political player of today, SEIU 775, is named for 2001’s Initiative 775, which provided a way for long-term care workers to unionize and bargain with the state.

So Tuesday’s meeting of the Senate State Government, Tribal Affairs & Elections Committee was rich in irony when all three of those players testified in favor of a bill that would make putting an initiative on the ballot substantially more expensive and difficult. In recent years, as progressives built big majorities in the House and Senate and won over and over in the halls of Olympia, the initiative has largely become an expensive nuisance for the left.

The bill in question, Senate Bill 5973 from Sen. Javier Valdez, D-Seattle, chair of the committee, would do two things: Ban the practice of paying signature-gatherers by the signature, and require initiative sponsors to gather 1,000 signatures before submitting a proposed measure to the state. The sponsor and his allies bill these as commonsense reforms that would combat fraud and misleading signature-gathering tactics and discourage the practice of filing multiple versions of the same initiative in search of a favorable ballot title.

The practical effect, however, would be to drive up the cost of running an initiative campaign. We know some folks in the initiative business in other states that have made similar changes, and that’s what happened there. In Arizona, where Republican lawmakers made a similar set of changes because they were getting their asses kicked by progressives at the ballot box, it can cost as much as $12M to qualify an initiative. Strangely enough, signature-gatherers aren’t as productive when they’re paid by the hour.

The target of Valdez’s proposal was sitting in the hearing room on Tuesday. Brian Heywood, the founder of the conservative initiative machine Let’s Go Washington, has cracked the code of getting on the ballot cheaply. The suite of six initiatives LGW sent the 2024 Legislature cost about $6M total. Lawmakers approved three to keep them off the ballot. Defeating the other three, which would have gored some prize progressive oxen, cost north of $30M, with much of the money coming from those three players in the second paragraph. Some political operatives of our acquaintance made some bank on those campaigns, but the players in question would surely rather have spent that money elsewhere.

Heywood’s many critics dismiss him as a rich-guy dilettante, but it’s clear that his wealth — or at least his willingness to spend it on initiative politics — has limits. Moneywise, LGW was badly outgunned in 2024.

The ballot initiative is by definition the province of the politically disenfranchised, if not the financially disenfranchised, and thus not beloved by folks in power. It has frequently been a way for corporate players to get their way: For example, Big Soda used it to pave over local sweetened beverage taxes and Costco went long to break the state monopoly on the wholesale and retail liquor markets.1 But it also gave us a high minimum wage, legal weed, gun control, campaign finance law, the Public Disclosure Act and a variety of measures aimed at keeping our taxes low, none of which would have passed the Legislature at the time they were proposed.

In an eyebrow-raising move, Valdez kept Secretary of State Steve Hobbs, a Democrat2, and former GOP Secretary of State Sam Reed (an elder statesman of moderate governance at 85) waiting while proponents of the initiative spoke first.3 Neither had anything good to say about the proposal. Both dismissed the notion that signature-gathering fraud was a problem and defended the initiative as the people’s check on its government.

“Pardon me for saying it, Mr. Chairman, but it’s a voter suppression bill,” Reed said.

Valdez’s measure is scheduled for a vote on Friday, which indicates this idea might have legs. Rep. Sharlett Mena, D-Tacoma, the chair of House State Government & Tribal Affairs, has a companion measure. Lawmakers have shown willingness in recent years to chip away at the initiative, most notably via the newish requirement that ballot titles carry a warning label about a measure’s impact on state spending.

PQ

What to do about that tort liability bomb

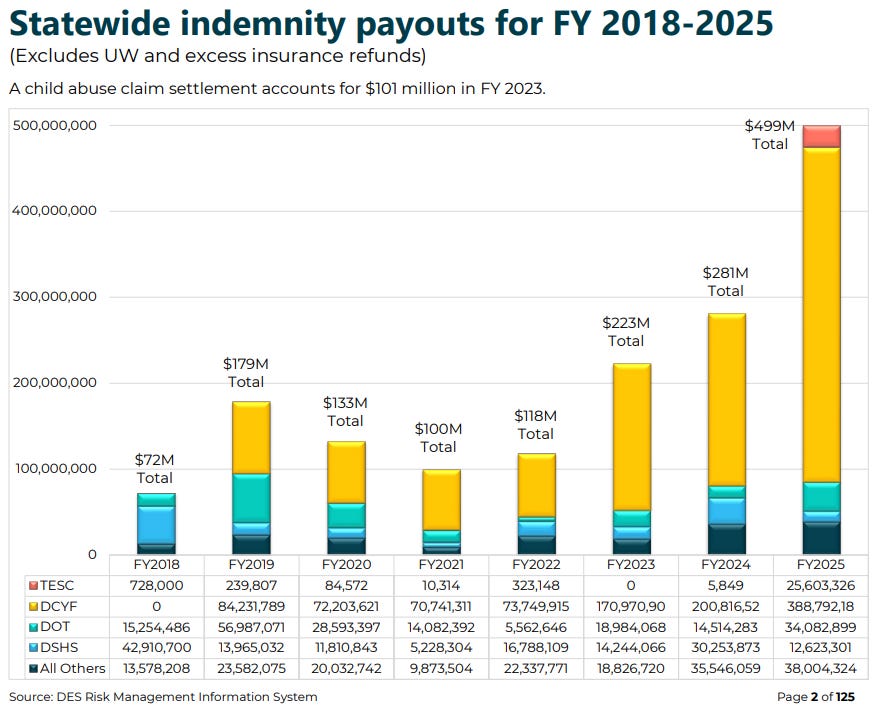

Addressing the financial bomb from lawsuits against the state is proving to be a bipartisan thing, if not quite a kumbaya moment in Olympia. The size of the bomb helps clarify the problem: the state’s cost to settle claims, mostly by former foster kids abused, neglected or killed in state care, has tripled since 2020 to $500 million last year. By 2030, the state’s self-insurance fund could be $3 billion in the red, or more.

The main bill to address the problem dropped this week from Sen. Manka Dhingra, D-Redmond, and Sen. Jamie Pedersen, D-Seattle. It would, for the first time, require all claims be put through a civil arbitration process, which could be the first or last stop in litigation. It is notable that the bill expands this step to all tort claims against all levels of government — from weed control districts to the Department of Children, Youth and Families — after Dhingra heard an earful from counties and cities dealing with their own liability bombs.

Quick background: The state (and other governments) are in this spot because a) public employees screwed up; b) WA, unlike other states, waived sovereign immunity eons ago; c) there’s been a series of state Supreme Court rulings and some legislation4 which expanded the type of cases that can be filed. The expansion particularly gave refuge to older (as old as the 1960s) claims of sexual abuse. In short, WA left itself exposed, and is reckoning with the extent of the sunburn.

The lobbying for and against the bill is just beginning, with the Washington State Association for Justice (lawyers who represent plaintiffs) flexing its considerable political heft against fiscal hawks, cities and counties, school districts, insurance pools and such. The trial lawyers are gold-tier-level supporters of the Democratic majorities and will now see loyalty put to the test. And now that the bill is ink-to-paper, expect to see victims’ rights groups weighing in to protect their right to be made whole.

The bill doesn’t ban anyone from turning down an arbitrator’s ruling and going to court. But there are a host of logistical and financial questions, including which courts would hear the arbitration cases. It’s not clear in the bill, but Dhingra envisions Superior Court judges hearing them. If so, that would funnel thousands of lawsuits involving government misconduct through a currently narrow legal channel, requiring more judges. That would be a whopper fiscal note.

An early estimate finds the bill could save the state 7% or more on the cost of payouts; that would’ve been $35M last year, and it might not be enough to convince lawmakers that the problem is solved. The savings would come in part by making lawsuit resolution more clinical – an arbitrator, after all, is not a jury being swayed by grueling emotional testimony from victims. The bill is also a relief to municipalities who feared they could be cut out. Sen. John Braun, R-Centralia, agreed that dealing with the liability bomb is a priority and isn’t opposed to Dhingra’s approach, but said it doesn’t address root causes for all those lawsuits.

Other liability-related bills running through the sausage-maker in Olympia include Rep. Amy Walen’s bill to require disclosure of who’s actually paying for lawsuits, and Rep. David Hackney’s proposal to exempt state and local correctional facilities from liability if an inmate died of a drug overdose by their own hand.

We heard from multiple sources that Gov. Bob Ferguson’s office originally floated a much broader tort reform proposal, including caps on damages and limits on sovereign immunity. We couldn’t find paper to back up, but Dhingra noted that WA is an outlier in the extent of its exposure. “We’re still a state opening ourselves to quite a bit of liability, but we’re balancing fiscal accountability with the rights victims have.”

JM

A chancy short-term rental tax

Killing a bill can come with a considerable down payment when you’re playing against the Legislature. Take the latest bid to tax short-term rentals.

For several years running, lawmakers have floated a 4% tax on renting out spare bedrooms, backyard cottages and second homes. Local governments would be the ones to pull the trigger on said tax under House Bill 2559 from Rep. Lisa Parshley, D-Olympia, which would steer the revenue into affordable housing ventures — e.g. tenant assistance, home repairs, etc. The idea is gravy with local electeds balancing budgets and a headache for short-term rental marketplaces like, say, Airbnb.

The bill got its day in the House Finance Committee on Tuesday where no shortage of Airbnb hosts were thumbs down on another cost of doing business. Meanwhile, the monied opposition in this fight is gearing up.

Here’s why you should care about this: Consider the following Exhibit A for how the powers that be in Olympia grease the gears of the legislative process behind the velvet curtain.

Airbnb is putting $1.9M into the already cash-laden PAC it assembled to put the tax above six feet under. This maneuver dovetails with the company’s blueprint to take the proposal to the ballot in the event it actually did get Gov. Bob Ferguson’s John Hancock.

Polling for Airbnb by EMC Research and Fulcrum Strategic shows some 60 percent of those surveyed were a hard nope on such a tax, mostly on the basis that their vacation bills will go up. Only one in four said they’d be more likely to vote for an elected who supported the tax, which is estimated to bring in north of $20M near-term.

Little of that is music to your average lawmakers’ ears. The state wouldn’t get a dime from the tax and would likely bear administrative costs in the near-term. That said, the vast swathe of local governments far from tech hubs like Seattle have few ways to keep the lights on.

The situation amounts to another high-level litmus test for how far Olympia’s leftward tilt has pushed tax-friendly Democrats. Money talks.

TG

Thanks for your attention. This is a free edition of The Washington Observer, an independent newsletter on politics, government, and the influence thereof. It’s made possible by our paid subscribers. If you’re not among them go ahead and hit the button to get access to all our stuff and the warm glow of supporting independent journalism.

When formal wear works for all occasions

The always tuxedo-clad Vanzetti, courtesy of his human, Melissa Davis. (Yes, there is a brother named Sacco for all you students of Depression-era history relevant to today’s events.) Want to see your pet in this space? Drop us a photo and some caption material.

Costco went long because its first attempt, the year prior, was derailed by a competing liquor-monopoly reform that confused voters. The idea that the liquor store should be open when an adult might run out of whiskey turned out to be broadly popular.

As a state senator, Hobbs was moderate thorn in progressives’ sides. Former Gov. Jay Inslee appointed him Secretary of State to get his vote out of the Legislature.

We’re told Valdez always lets the proponents speak first, even when he disagrees with the bill.

We’re not lawyers here at The Observer, but a DCYF funding request includes what seems like a decent rundown of the court rulings that expanded liability. The 2024 bill to waive the statute of limitations on childhood sexual abuse lawsuits passed unanimously, so there’s no partisan fingerpointing allowed.