Will we see the capital gains tax on the ballot?

Some 17,000 people have 500 million reasons to force a public vote

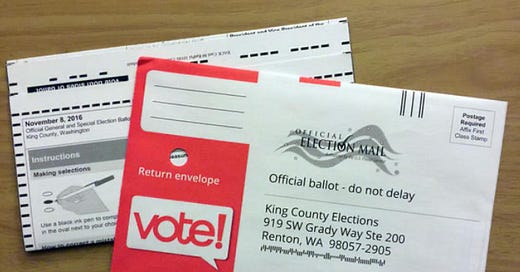

When the Senate narrowly approved a capital gains tax on Saturday, they all but invited two challenges to the measure, should it become law: A legal argument that it violates the constitution and a referendum to force a statewide vote in November.

We’ll dig into the constitutional challenge another day because the referendum poses the more immediate thre…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Washington Observer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.