Fact-checking the farmworker union debate

Plus surveillance, législative records, lobbyist photographs, and the quote of the week

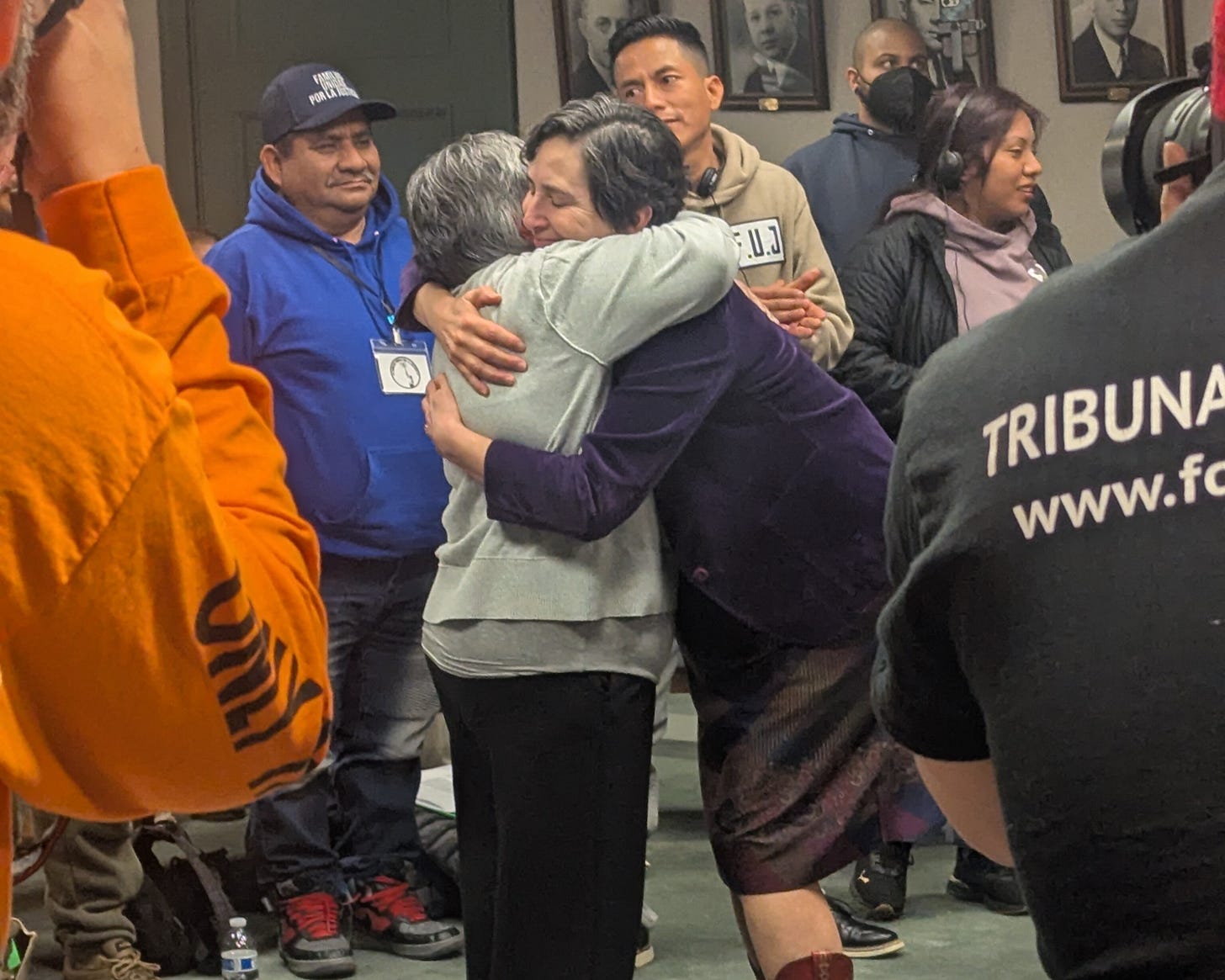

Farmworker union Familias Unidas Por La Justicia and farm owners packed the Legislature’s hearing rooms last week to testify about SB 6045 and HB 2409, which would give farmworkers more collective bargaining rights. Here’s an Observer fact-check on some claims made during those hearings.

“Striking during harvest would threaten the small window of time farmers have to produce their income for the entire year,” said Bre Elsey, director of governmental affairs for the Washington Farm Bureau.

Farmers used variations of her argument over and over again during the hearings. The implication is that giving workers additional collective bargaining rights equals giving them the right to strike with impunity. That’s wrong, and is based on a misunderstanding of what the bill actually does, existing state law, and a bleak economic environment for farmers. Before launching into the nitty-gritty, here’s the short version: workers, unionized or not, can strike whenever they want, even during harvest. They’d risk employer retaliation, but they absolutely can go for it. In fact, many of the more famous strikes in the history of the American labor movement predated any formal collective bargaining laws.

Now for the nitty-gritty. The bills are looking to counteract agricultural workers’ exclusion from the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, which has been a thorn in the palm of farmworker advocates for generations going back to César Chávez. That act created the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and put it in charge of enforcing private workers’ rights. Since agricultural workers are excluded from the NLRA, they don’t get all that institutional protection the agency gives other private employees. Public employees are also exempted from the NLRB, but usually have some sort of state body that does the NLRB’s job. In Washington, that’s the Public Employment Relations Commission (PERC). What these bills do is place agricultural workers within the jurisdiction of PERC, giving the workers a body that can enforce workers’ rights since the NLRB doesn’t.

That would be a sea change for farmworkers, and it reflects a shift within the Legislature. The Senate sponsor of the bill, Labor & Commerce Committee Chair Rebecca Saldaña, D-Seattle, is both the daughter of a farmworker and a former union organizer. As recently as 2017, the chair of that committee was a conservative farmer and such ideas died fast and quiet.

At the state level, workers have the right to form a union and do collective bargaining activities, like a strike. That’s how unions like Familias Unidas Por La Justicia exist despite being excluded from the NLRB.

Generally, most union contracts also have a no-strike clause that’s agreed upon by both the employer and employees during contract negotiations. It does exactly what it sounds like, prohibiting employees from striking during the duration of a contract. Familias Unidas has one of those clauses in its contract with Sakuma Bros. Berry Farm.

A few testifiers said the bill pushes card-check certification instead of secret ballot elections, which is misleading. The bill copies the process PERC uses for public employees, which uses card-check as a default, but includes secret ballot elections under certain conditions.

At PERC, the unionization process starts with a petition from employees, usually by signing cards that show interest in organizing. Once 30% of employees sign, PERC notifies the employer by asking for a list of employees. If more than 50% of employees signed, PERC conducts what’s called a card check, which certifies the union. A secret ballot election, where PERC gives employees a ballot with instructions, happens if less than 50% of employees sign, or if there’s more than one union interested in getting in on the action.

The farm owners at the hearing raised concerns that card-check brings up privacy issues and the possibility of employees coercing each other. Unions will generally argue the opposite, that a secret ballot election allows employers to persuade their employees not to unionize. When card-check certification happens, employers aren’t notified about the process until after the cards are submitted to PERC. Unionization can happen under the employer’s noses, removing them from the process until the actual contract negotiation.

To cut the farm owners a bit of slack, one resounding concern was based in reality. Farming has been getting more expensive for farm owners. That’s due to a myriad of factors including tariffs, wage increases and rising costs for equipment and transport. In 2024, Washington ranked last among the states in farm owner take-home pay. At the same time, though, union contracts like the one Familias Unidas won don’t necessarily guarantee a living wage for the workers either. Their contract got them a whopping $15 per hour. There’s no easy solution to increase everybody’s quality of life.

RHM

Bipartisan support for limits on license plate readers

As it turns out, folks on both sides of the aisle aren’t big fans of surveillance, at least when it comes to license plate readers. SB 6002, which would mostly ban the cameras, managed to unite co-sponsors Sen. Yasmin Trudeau, D-Tacoma, and Sen. Jeff Holy, R-Cheney last week, as well as the entire Senate Law & Justice committee except for Sen. Nikki Torres, R-Pasco.

The bill prohibits most uses of automated license plate readers, but carves out exceptions for law enforcement investigating stolen vehicles and missing persons, parking enforcement activities, and toll enforcement systems. Notably, it exempts data from the cameras from public records laws, and immigration enforcement is specifically prohibited from using it.

Legislators added one major amendment before the bill moved to the rules committee. Originally, data from allowed cameras had to be deleted within 72 hours. Now it’s 21 days.

For Democrats, the bill protects favored constituencies, including immigrants being tracked by ICE, people getting abortions outside of their home states and people looking for gender-affirming care.

For Republicans, it’s a personal privacy issue. Holy, a former police officer, addressed surprise that he was co-sponsoring the bill, saying, “Are we seriously going to argue that people don’t have a reasonable expectation of privacy when it comes to every single movement being tracked?” On the immigration front, Holy said the bill doesn’t do anything the Keep Washington Working Act hasn’t already done.

The bill is part of ICE’s looming presence over this year’s legislative session. Bills to ban masks for law enforcement and prohibiting ICE agents from acting as law enforcement have been advancing. Gov. Bob Ferguson also discussed using Washington’s National Guard if ICE activity escalates in the State during a press conference earlier this week.

RHM

Lawmakers are still trying to hide their records

The Legislature’s ongoing effort to throw a veil over its records is back in court on Thursday, but it’s most definitely not going to be the last stop in the legal food fight between lawmakers and public records enthusiasts. This issue seems destined for a date at the Temple of Justice, so we’re not going too deep in the weeds.

A case1 being heard in the Court of Appeals, filed by public records advocate Jamie Nixon and the Washington Coalition for Open Government, centers on lawmakers’ efforts to invoke a “legislative privilege.” You won’t find that anywhere in the Public Records Act, but that hasn’t deterred lawmakers from breaking out the redaction sharpies when – or even if – they release emails.

Lawmakers explicitly tried to give themselves a pass from the Public Records Act with a 2019 law, but Gov. Jay Inslee vetoed the bill amid populist outrage fomented by newspaper editorial boards across the state. But the issue didn’t die.

At the heart of the case is the question of whether the horse-trading work of legislating is better, or rightfully, done behind a veil. We here at the Observer have some thoughts on that, but to be fair to lawmakers, the state did score a win at the trial court.

We’ll spare you the legal wrangling, but much of it centers on the state Constitution’s “speech and debate” clause and leads to obscure references to colonial-era House of Commons sausage-making and the intentions of the cheeseheads in Wisconsin, from whom we copied that clause.

One interesting argument from the public records attorney, Joan Mell, is that individual lawmakers apply the newfangled legislative privilege in wildly different ways. Some simply deny and deflect. Some release heavily redacted emails. Others are far more transparent. It is a wild west of application, which doesn’t make for the strongest argument if you’re trying to carve yourself out of the records act.

There is a second case being heard Thursday, also brought by Nixon, about an auto-delete function baked into state agencies’ Microsoft Teams apps. That let chats, presumably about important policies or (we hope) spicy gossip, disappear after seven days, until Shauna Sowersby, then at McClatchy, reported on the retention schedule scandal. Among the state’s arguments is that it can’t be liable – i.e. pay penalties – for records that no longer exist.

Again, we here at the Observer have some thoughts on disappearing records without so much as an oopsie. The public can’t ask for records it doesn’t know exist. And it makes us wonder what other types of messaging apps are deleting records like a bug zapper. But, to be fair to the state, it also won at the trial court, sending this one to AA ball and the court of appeals.

Regardless of what the appeals court does, TVW will undoubtedly be airing the main event at the state Supreme Court, maybe later this year. Worth noting: the Supremes, in that 2019 fight, said the Public Records Act does apply to lawmakers, but that was clearly not the last word on the matter.

JM

A gallery of lobbyists

We here at the Observer — and most journalists everywhere, for the most part — do what we do because we want to have an impact. Make things work better. Transparency. Yada yada.

So, with a glow of pride, we note that the Public Disclosure Commission updated its lobbyist directory to make it easier to review photos of the members of the Third House2 on the landing page. We’d asked if the PDC had something like a lobbyist yearbook, and voila, those hardworking folks answered. Next edition, we’ll hope for Best Smile and Most Likely to Go Viral, but at least for now, we’ll be able to put more faces to names. You’re welcome.

JM

Quote of the week

A Senate Law & Justice committee hearing Tuesday morning on Sen. Manka Dhingra’s bill to cool down the tort liability bomb exploding state and local government budgets drew a parade of plaintiffs’ lawyers to the testimony table to argue against tilting the legal table against people suing for the redress of wrongs. Attorney Ryan Dreveskracht of the Galanda Broadman law firm said the silent part out loud about the plaintiff bar’s longstanding and deep-pocketed support for Democrats.

“Simply put, it’s the antithesis of what we voted for and campaigned to put you in office.”

JM

Recommended Reading: Taxing AI factories

Conrad Swanson with The Seattle Times Climate Lab team tees up proposals from Sen. Sharon Shewmake, D-Bellingham, and Rep. Beth Doglio, D-Olympia, to slap an energy tariff on power-hogging data centers, to force them to buy clean energy, and to disclose their power and water use. The general ideas have kicked around for a while, but got an extra oomph with a 2024 Seattle Times investigation3 that found data centers were imperiling the state’s green energy goals, and an ensuing task force that looked at the AI factories’ strain on the grid.

The bills undoubtedly will have populist appeal, easing the potential that utilities will jack up rates on “grandma” to meet the gargantuan demand, as well as the potential for revenue. But queue up pushback from Big Tech, and from the Central Washington towns that raked in property tax revenue from data centers. The industry is already looking askance at Gov. Bob Ferguson’s proposal to close a data center tax loophole.

JM

Why can’t Washingtonians grow their own weed?

Aspen Ford over at the Washington State Standard makes her first appearance in this section by breaking down one of the weirdest aspects of the state’s cannabis laws: In a state awash in weed, it remains illegal to grow your own. This issue dates back to the 2012 ballot initiative that legalized recreational marijuana in Washington, which was an awkward alliance of those who wanted legalization for purposes of getting high, those looking to make bank in a legal market, and folks looking to get rid of the human and financial costs of locking people up for weed-related offenses. Those strange bedfellows landed on a tightly regulated system. Growing your own was a casualty.

PQ

Thanks for your attention. This is a free edition of The Washington Observer, an independent newsletter on politics, government, and the influence thereof. It’s made possible by our paid subscribers. If you’re not among them go ahead and hit the button to get access to all our stuff and the warm glow of supporting independent journalism.

Who doesn’t like a cozy bed on a wet winter day?

Kobe chilling in Paul’s office at Observer World Headquarters. Want to see your pet in this space? Drop us a photo and some caption materials.

There’s a very similar case on legislative privilege filed by public records pitbull Arthur West. It was heard in December.

This term for the paid advocates who pace the statehouse marble used to be in more common use. It’s reflective of the fact that many lobbyists have been around longer than all but the most senior lawmakers and wield significant influence. There are badges and everything.

Disclosure: Jonathan edited that Times project, so we know Gov. Inslee’s administration vehemently disagreed with the investigation’s findings, and find it gratifying that the notion of adding the equivalent of four Seattles to the power grid by 2030 – the potential load from the growing data center market – is finally being acknowledged as, uh, a problem.